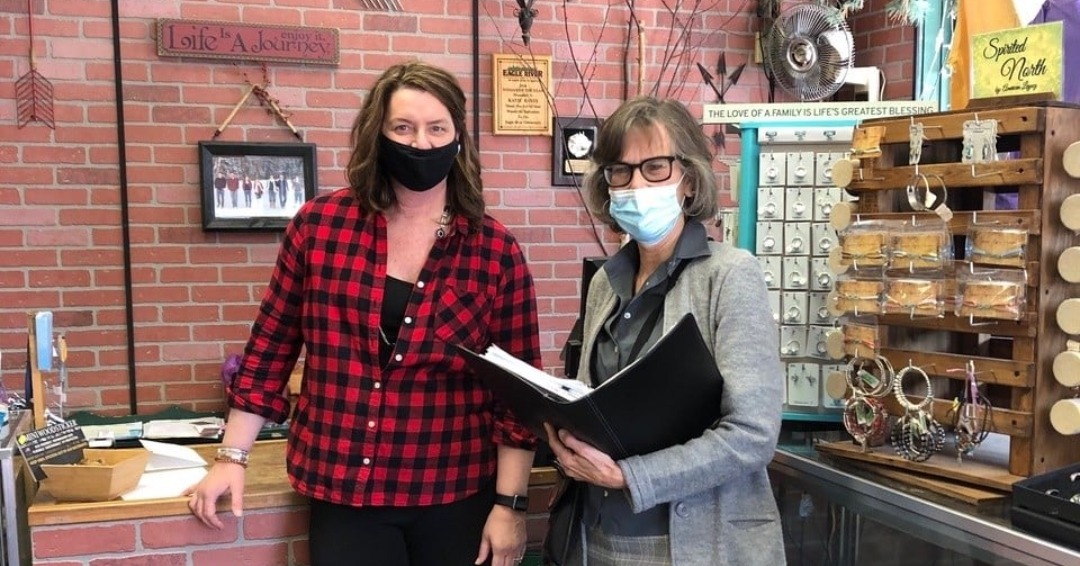

Connecting growing businesses such as Eagle River’s Arrow Gift Shop with tools and resources helps businesses grow, evolve and transition, as needed. Retaining key anchor businesses brings foot traffic to the district and creates a pool of local business mentors to support future startups. Photo courtesy of Retailworks, Inc.

The COVID-19 pandemic foisted many dizzying changes on locally owned businesses, including temporary and permanent closures, changing entrepreneur demographics, labor market shifts and a switch to online sales. One benefit of coordinating a long-standing program such as Wisconsin Main Street (celebrating its 35th year in 2022) is the ability to explore trends over time. A recently completed study by Wisconsin Main Street illustrates the nature of entrepreneurship over the past three years in Main Street districts. It highlights many changes in the small business world, but also points to the critical importance of downtowns in cultivating and supporting entrepreneurs and building a vibrant small business environment that fosters new business innovation.

Let’s take a look at some the report’s key findings and strategies that communities can use to bolster their entrepreneurial support efforts.

A look at downtown entrepreneurs

Maranta Plant Shop opened in 2021 in Milwaukee’s Historic King Drive District, filling a gap in the marketplace. The shop utilized a Kiva matching loan to open its permanent storefront after opening as a pop-up the prior year.

Downtown entrepreneurs are as diverse as their communities.

Individuals choosing a downtown location do so for the affordable space options, existing foot traffic, the potential to co-locate with complementary businesses and to enjoy a supportive network of like-minded small businesses.

The study found women remain prominent in downtown entrepreneurship, representing more than 38% of reported startups—51% including jointly owned businesses. This compares to 39% of all existing downtown businesses owned or led by a woman.

The strength of women’s ownership crosses all industry sectors, with more than 20% of businesses in all sectors wholly or partially owned by women. While women have consistently been a strong presence as downtown business owners relative to other business sectors, the number of minority-owned businesses in downtown is growing. The number of minority-owned startups identified in the 2022 study were 50% greater than the number of businesses reported in 2018, although not yet reaching the 13% of all Wisconsin small businesses owned by minorities.

Minority business owners were concentrated in retail, personal services and restaurant sectors, with 18% of all restaurants started by minority owners.

Regardless of race and gender, individuals come to entrepreneurship on a variety of paths. There was speculation that post-pandemic entrepreneurs would include a larger share of second-career or pivoting-career entrepreneurs, but this study refuted that hypothesis, at least as it pertains to downtown businesses. Once again, first-time entrepreneurs represented the bulk of new business activity—35% of all new businesses—especially in rural areas where businesses are twice as likely to be started by early-career or first-time entrepreneurs. Second-career entrepreneurs represent 13% of business owners and were most likely to open bars, especially breweries, and retail shops and least likely to open service businesses. In contrast, serial entrepreneurs, those that have started or owned businesses previously, are focused on urban areas and favor the bar, entertainment and hospitality sectors which tend to be high-capital and high-risk ventures.

The broad cross-section of individuals with the potential to start a downtown business shows the importance of consistent and proactive outreach and messaging about the benefits and opportunities available for businesses in downtown.

Finding ways to support local entrepreneurship

Copper Pasty in Ashland is one of numerous market vendors that moved into a permanent storefront this past year, illustrating one common entrepreneurial pathway for downtown businesses.

The year-over-year growth in business startups during the past six years and beyond points to the desirability of a downtown business location for many entrepreneurs.

Startup activity and business viability, however, are not always correlated. For each of the three-year study periods, 10% of businesses that opened during the study period closed within the 36-month survey window. For all closed businesses, the average tenure is 8.3 years, aside from a drop to 6.3 years during the peak of pandemic business closures.

Some businesses face greater hurdles than others, as minority businesses experienced a higher closure rate, with 13.2% of new minority-owned businesses closing during the study period. Similarly, the average tenure of minority-owned businesses that closed was only 2.3 years, significantly less than for the entire startup population.

Business startup and growth activity are critical to the long-term economic viability not only of downtown, but also the entire community. Locally owned businesses generate revenue for property owners, business service providers, and contribute to the local tax base, often at a far greater rate than chain businesses.

According to 2017 data from the Brandow Company, a typical 2,000-square-foot retail business spends $8,000 to $10,000 annually on goods and services that are often purchased locally. These businesses also create a daytime customer base that supports restaurant and retail spending. Although individually they employ a handful of people, the collective impact is significant, with Wisconsin downtowns accommodating 16% of all business entities and corresponding levels of employment within a given municipality.

In addition to the financial benefits generated by downtown businesses, their civic contributions are also significant. Women-owned businesses tend to be highly engaged in the community, with half of new business owners but 70% of women-led startups actively involved in the community, serving on a municipal or civic board or committee. A significant share of local businesses also sponsor and support other community and civic initiatives, enhancing the local quality of life.

There are many ways that communities and districts can proactively support small business activity. These might include a combination of policies, programs and capital.

One important, but often-overlooked, aspect of entrepreneurial development is the fairly lengthy pipeline from potential new businesses to pass from the planning phase—when a business first contacted local representatives for information—and occupancy and opening.

Not all businesses engaged local stakeholders prior to opening, but this information was available for one-third of all reported new businesses. The average business tackled multiple processes such as permitting, buildout and financing within eight months. Meanwhile, 36% took more than one year to open their doors, and 9% took several years to find the right location and complete buildout.

This interim period is a critical timeframe for entrepreneurs, as they are actively exploring business concepts and locations. Communities that have a process for remaining in contact with prospects have a greater likelihood of not only landing the business, but also of being able to connect the entrepreneur with resources that will make them more successful.

The availability of quality move-in-ready spaces is another limitation on startup activity for some communities. Not surprisingly, 76% of startups rent rather than own their spaces. However, entertainment, hospitality, bar and restaurant businesses were significantly more likely to own rather than rent. (more than 2/3 of businesses in each category occupy owned properties). These businesses tend to require higher capital outlays and are often perceived as riskier by lenders, making owned real estate as valuable as collateral.

Rural businesses owners, however, were twice as likely to purchase properties as urban businesses, with just over one-third of rural businesses purchasing spaces to open their business. While property ownership is generally a positive trend, providing cost efficiencies—such as the ability to live above one’s business, increasing financial stability by minimizing rent increases and/or introducing additional revenue streams from ancillary residential or commercial tenant rent—the tendency toward ownership in rural areas may not always be by choice.

In many small communities, the availability of suitable spaces for new business ventures is limited. Older properties in need of maintenance, coupled with cash-strapped property owners, often require new rental tenants to make significant investments in space upgrades in exchange for reduced rent. But this arrangement increases overall startup cost and uncertainty.

Programs that provide financial incentives for landlords and/or tenants to renovate and update spaces can be effective strategies for creating opportunities for would-be entrepreneurs. Similarly, connecting landlords or potential businesses with resources such as local artists, technical college construction or architecture programs, and real estate attorneys to identify and mitigate the most challenging constraints can also be effective at leveling the playing field.

Previous studies have illustrated the importance of public financial support for property rehabilitation projects, with 66% of property renovations using some form of local assistance to fully renovate vacant or underused properties. This year’s startup study also explored the receipt of public funds by new businesses. Relevant assistance included startup help such as façade or signage grants or loans, but also local COVID relief funds (federal or state funds were not included). Fully 35% of newly opened businesses reported receiving some type of financial assistance, including the 8% that received Tax Increment Finance funds or other renovation loans, while 35% received façade or sign grants, and 57% getting COVID-19 relief funds.

Businesses in every sector received assistance, but businesses in urban settings were twice as likely to receive local financial incentives for both startup expenses and COVID-19 relief. Access to funds seemed to impact business viability, as fewer than 7% of businesses receiving financial assistance closed during the study period. Creating a pool of affordable and available funds, whether public, public-private or strictly private, reduces the out-of-pocket startup costs and ensures that businesses can complete all necessary investments to maximize their chance of success.

Examining emerging downtown trends

The 2021 Downtown Pitch Contest winner, Chef Pam’s Kitchen in Waukesha, is an example of a growing trend of entertainment and experiential businesses opening in downtown districts.

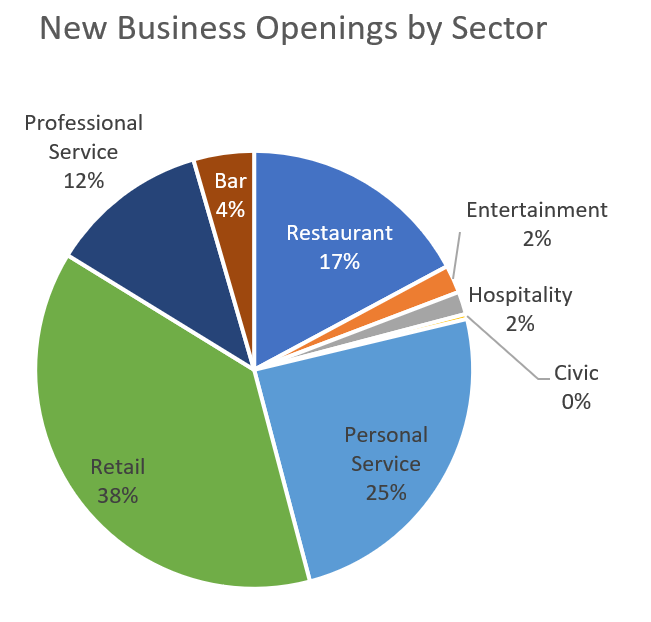

The mix of businesses opening in downtown districts is incredibly diverse, with a wide variety of industries, ownership structures and investment outlays. While the share of businesses within broad industry categories has remained consistent over the various study periods (illustrated in the accompanying chart),  the mix of businesses within these categories has shifted significantly.

the mix of businesses within these categories has shifted significantly.

The pandemic clearly had an impact on business openings and closings, although not in the way that many expected. While there was a lull in startups in the restaurant, bar and personal services sectors during 2020, new starts in 2021 in these segments made up for this shortfall. Some business sub-types did close at higher rates due to the impact of COVID-19, especially fitness studios, while other businesses opened at greater rates, including education and childcare.

Restaurants, an oft-referenced pandemic-sensitive industry, represented an equal share of opening and closing activity over the three-year period, although the actual ratio of restaurants closing to opening was 2:1, as some restaurants pivoted while other concepts emerged.

New business types continued to emerge and evolve in the entertainment space. For bars, closures were most common for lounges and clubs, while sports bars, pubs and breweries—25% of all openings—stepped in to take their place. Non-bar entertainment also increased substantially, with a mix of museums, axe throwing, arcades and experiential businesses featuring art, cooking and other activities abounded. While some of these business types had opened in previous years, non-bar entertainment represented only 12% of the category in 2018 and 35% in 2022.

Retail startups were slightly depressed in 2020, but 2021 saw the highest rate of retail openings of the past decade. Dominant business types included ever-present apparel and gift as well as numerous nutrition shops, home goods, bakeries and CBD stores continued to multiply. Antique stores and used merchandise businesses were heavily represented in retail closures.

As previously mentioned, fitness and salon businesses were hard hit by COVID, comprising more than half of closures in the personal services sector. In contrast, mental health was an emerging business sub-category, representing 10% of startups in the category, including therapists and businesses marketed as mental health services, such as salt rooms). The photography, childcare/child enrichment and education/tutoring categories also welcomed numerous businesses to downtowns in the past three years.

With a few previously identified exceptions, the annualized rate of closures was fairly consistent over the study period, with 8% of new businesses closing in the first year. Just over half of closures occurred in businesses that had been open more than one but less than six years, 16% in businesses with 6-10 years of experience, and 21% in businesses established more than a decade ago.

This last category has been inching upward as baby boomers continue to retire, in many cases with no established succession plan. It remains to be seen what impact, if any, revenue setbacks will have on the retirement plans of these business owners.

Geographically, rural districts have traditionally outperformed urban neighborhoods in startup activity. However, this most recent study found fewer startups in rural communities. It is unclear if this decrease is due to space availability, capital limitations on property purchases, lack of local financial support, industry trends favoring urban businesses (75% of entertainment venues open in urban districts) or some other constraint. Despite the slightly depressed startup activity, rural businesses remained more resilient, with closure rates 10% below urban areas.

There is value to communities in understanding the opportunities and constraints associated with opening and operating a business given the location and available properties. The information from this study can help identify potential tenant types and entrepreneur profiles that may be a good fit for a particular community. From there, communicating opportunities by casting a wide net ensures that would-be entrepreneurs are both aware of and inspired to consider local possibilities.