By Joe Lawniczak, WEDC Downtown Design Specialist

Established in 1976 at the federal level, historic rehabilitation tax credits have contributed to the restoration, renovation, rehabilitation, and reuse of countless historic buildings across the country, including in Wisconsin—projects that would otherwise have been cost-prohibitive. These credits are available to owners of buildings that are individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places, are deemed eligible for listing, or are a contributing part of a National Register historic district. If the building owner applies for these credits and their renovation plans are approved, they can claim a credit on their federal income taxes for 20% of the eligible renovation costs. These federal credits can then be carried forward up to 20 years and carried back one year.

Unfortunately, the federal tax credit program has requirements that can make claiming these credits tedious, time-consuming, and complex, particularly for owners who are not developers by trade. For example, the formal application and design review process can take up to six months or more. Owners must also spend a minimum amount on the renovation in relation to the adjusted basis of the property, which can be complicated to compute. And if the owner doesn’t have enough tax liability to use the credits themselves and they instead wish to sell (subsidize) the credits, they must follow strict rules.

These complexities often require owners to seek the services of experienced professionals (architects, contractors, accountants, etc.) who know the nuances of the program. While architectural services are an eligible expense for the tax credits, these costs still posed an obstacle to using the credits on smaller-scale buildings; thus, prior to 1989 (when the federal credits were the only ones available) primarily experienced developers and larger buildings made up the bulk of the projects using the credits.

In 1989, Wisconsin began offering a supplemental 5% state tax credit (to be used in conjunction with the federal 20%) to provide an additional incentive for property owners to restore their buildings. While certainly a step forward, this state credit still wasn’t enough to tip the balance for many small projects to move forward. In 2013, Wisconsin increased the state credit to 20% to match the federal program, meaning property owners could get credits for up to 40% (20% state, 20% federal) of the renovation costs. This increase was a game-changer, as it made smaller-scale projects more financially feasible.

These smaller-scale renovations, with less than $250,000 in credits claimed, have become known as “small-deal” projects. Unfortunately, it is difficult for property owners to navigate both the complexities of the federal program and the slightly different rules of the state program on their own. Even so, thanks to the increased state credit, more and more owners are either learning the process or hiring professionals to help.

This month’s issue includes case studies of a handful of Wisconsin property owners who have successfully used historic tax credits. The first set of stories highlight the scope and scale of successful recent projects. Later stories explore some of the difficulties owners face in design, application, renovation, and tax filing—along with solutions. We hope this will inspire more owners in Wisconsin to pursue small-deal projects and prepare them for the challenges.

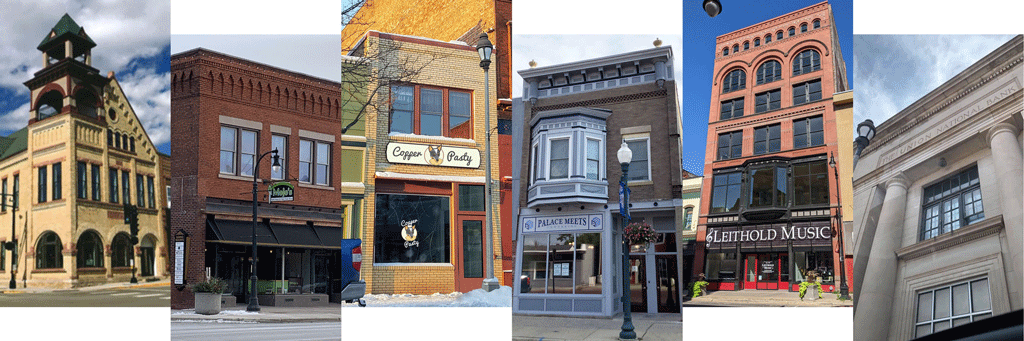

Libby Bros. Building – Evansville

Libby Bros. building before and during renovation

This 1903 building had seen better days. The storefront had been altered with tiny windows, the original character of the ground floor interior space was removed or covered over, the tin ceiling was damaged or removed in areas—and the clay tile entry floor was in poor shape. The new owners brought back the original storefront configuration, restoring the exterior’s grand 1903 appearance, and continued with interior work on the floors, ceiling, plumbing, electrical, and HVAC. The building now houses modern coworking space for small tech companies and startups. This was a true small-deal tax credit project in terms of renovation costs, as the credits used by the owners were under $40,000 each for federal and state. As mentioned in the introduction, prior to Wisconsin increasing the state credit to 20% in 2013, pursuing tax credits for this scale of project would likely not have been worth the time, effort, or expense–and therefore, this project may not have happened at all.

Libby Bros. building after renovation

Deming Building – Marshfield

Deming Building before and after façade renovation.

The Deming Building is an 11,000 square-foot building built in 1898 as a dry goods and clothing store with offices above, including the law offices of owner Edgar M. Deming. Through the 1990s, it hosted businesses including a barbershop, a variety store, and a photo shop. When Chris and Erin Howard purchased it in 2018, the building had fallen into disrepair after being mostly vacant for many years. The new owners began a complete renovation, and the building now houses seven office tenants, a restaurant, and a retail store. The renovation included accessibility upgrades, new restrooms, and much more, resulting in $200,000 worth of credits (evenly divided between federal and state). The Deming Building’s restoration also had a wider effect, as its location on a prominent corner of downtown Marshfield catalyzed other renovations in the district.

Deming Building after interior renovation and ADA improvements

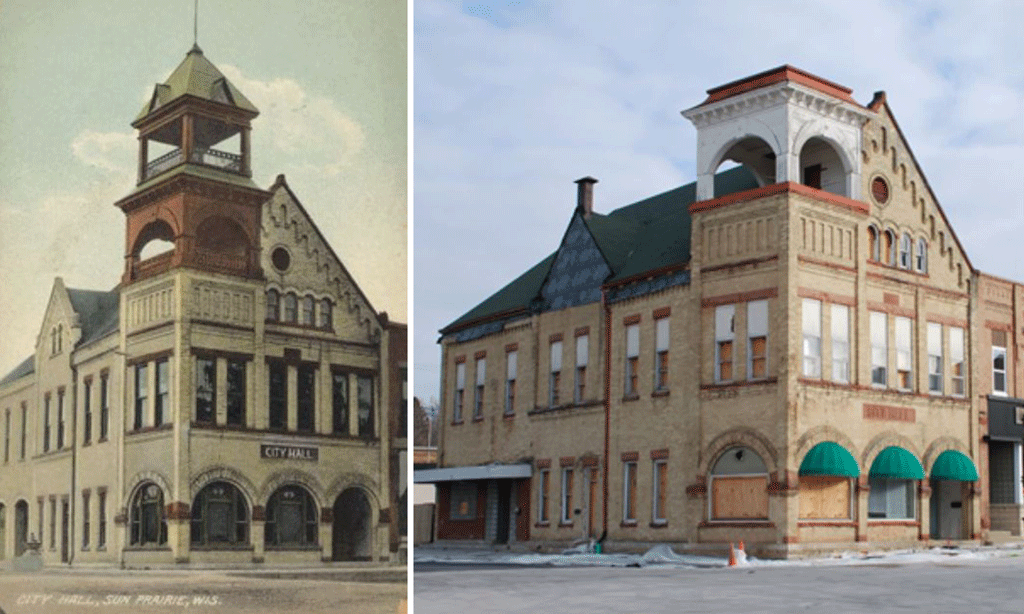

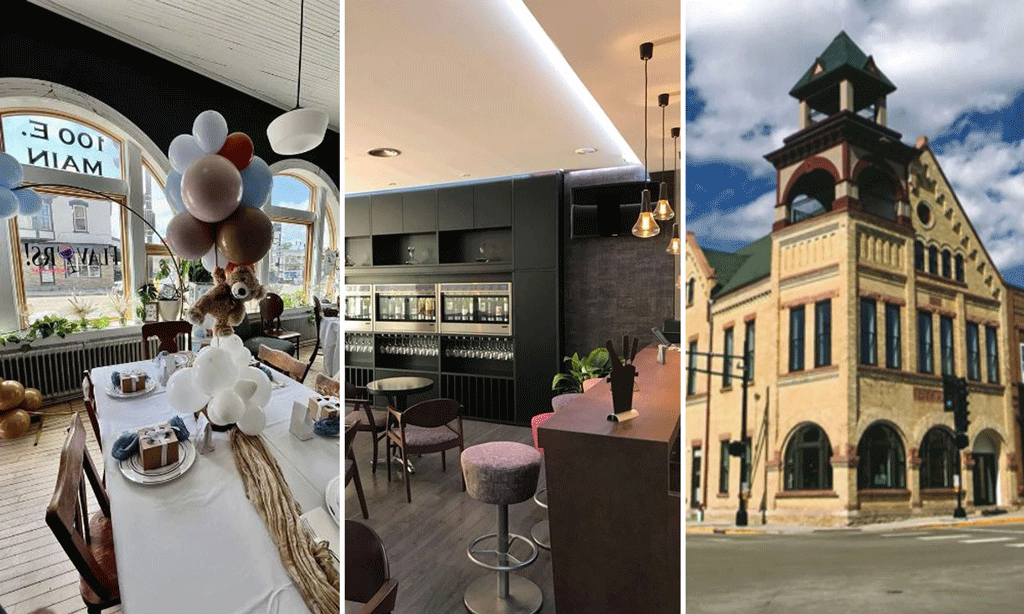

Old City Hall – Sun Prairie

Old City Hall before renovation (Left photo by Ron Tobia)

This example is just above the threshold of what is typically considered a small-deal project, but it is close enough and monumental enough to include here. Built in 1895, Old City Hall served as the city hall, jail, auditorium, and fire station until 1956, when the city constructed a new municipal building. It was then converted to ground-floor commercial space with apartments above. Over time, the building gradually deteriorated, saw alterations to its monumental clock tower, and was badly damaged from a 2018 gas explosion across the street, which lifted the entire roof off the walls and slammed it back down, damaging the bricks, joists, and trusses. After the explosion, Old City Hall and the remaining buildings in the area were added to the National Register, opening up the possibility of using historic tax credits. In response, the current owners restored the entire building, recreating the original 65-foot bell tower and second-floor auditorium hall, repairing blast damage, adding accessibility features, and more. The first floor was converted into Flavors Wine Bar; the upper hall is now used for weddings and events. The project used a total of $520,000 in tax credits ($260,000 each for state and federal).

Old City Hall after renovation

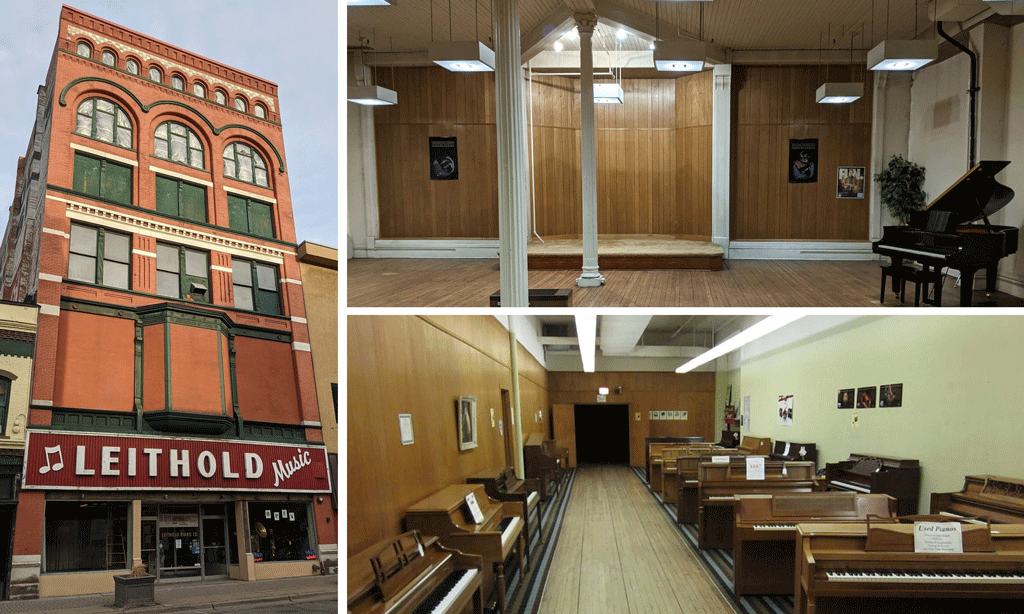

Leithold Music – La Crosse

Leithold Music before renovation

This impressive Romanesque Revival building was built in 1889, and amazingly, it has had only two owners in 135 years. For the first 73 years, Tillman Furniture built and owned this treasure, and for the past 62 years, it has been home to Leithold Music, where generations of area musicians got their start. The building fell victim to different trends over the decades (including wood paneling concealing the entire wall of second-floor windows) and, as a result, the owners felt it was time to bring back its original appearance. Working with Marc Zettler of Zettler Design Studio, they developed a plan and applied for façade and architectural/engineering grants from the city and for federal and state historic tax credits. Renovations began in September 2021, and when they removed the large sign covering the transom windows, they were delighted to find the original prism glass still intact underneath. They then applied the building’s new signage directly to the glass instead of once again covering it over. They also removed the white paint from the sandstone accents, renovated the storefront and upper windows, and uncovered the large second-floor windows overlooking Fourth Street—which made a dramatic difference inside and out—and completely enhanced the backdrop for the recital stage. The total tax credit amount for this impressive transformation was $208,000 (again, evenly divided between federal and state). Architect Marc Zettler’s experience with historic buildings and tax credits was essential in making the credits viable for this project, and the owners give him credit for doing 98% of the paperwork and submissions and for overseeing construction. This is an ideal case in which the combination of the tax credits, the Leithold family’s desire to bring the building back to its former glory, and Zettler’s invaluable expertise made for a truly amazing transformation. But as seen in the following case studies, the added costs of such expertise require many building owners in small-deal scenarios to personally learn the credit process as they go.

Leithold Music after renovation

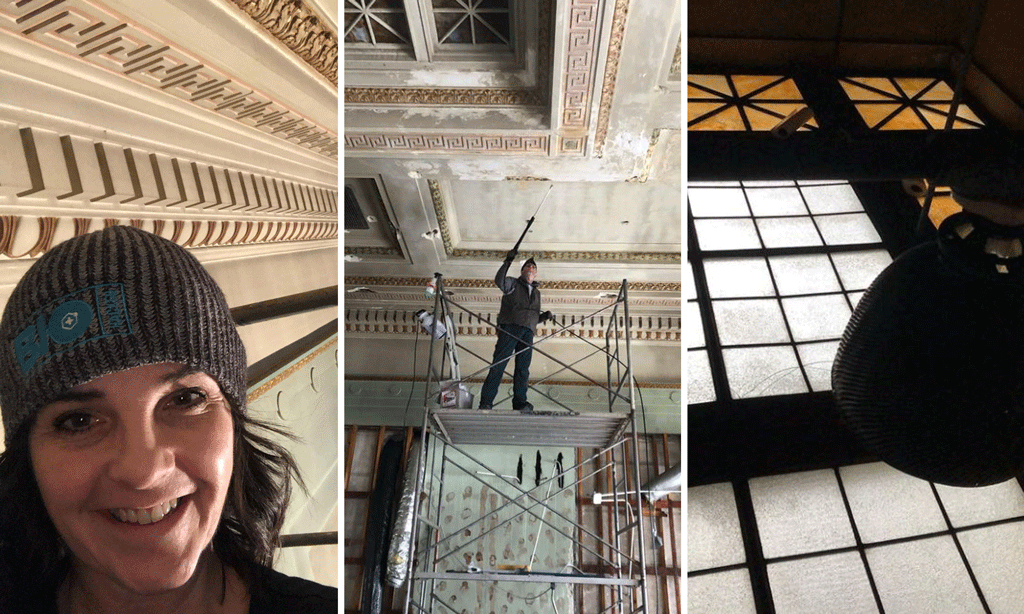

Union on Main – Ashland

Union on Main before renovation (Photo by Wisconsin Historical Society)

This former 1923 Union National Bank is being renovated into a women’s clothing boutique and a wedding and events venue. Vacant for 30 years, it required significant repair, maintenance, and restoration work, including new HVAC and roofing and repairs to the ceiling, ornate plasterwork, and a 100-year-old skylight. The owner, Jeanne Aspenson, undertook the monumental task of bringing this iconic corner building back to life, even helping with much of the renovation work herself. She’s not only utilizing historic tax credits, but she also received a $125,000 Community Development Investment Grant from WEDC.

From the beginning, Aspenson sought the assistance of local professionals and peers. Ashland’s city planner, Steven Wiley, helped her navigate the application process, and her architect, Amber Ericksen, helped with the first submissions. Jeanne also talked with fellow property owners Tim Pavlish and Elizabeth Andre about their experience with a recent tax credit project. But as a first-time applicant, Aspenson found the process was challenging enough to hire a consulting firm to help finish the first and second parts of the application. She also had to hire someone to help with the complicated process of submitting an amendment request, leaving her with unexpected costs that she struggled to afford.

The design review process brought additional challenges, as she found that neither side of the review process was willing or able to budge when code requirements and budget conflicted with historic review standards. Further, once she completed part two of the application, investors contacted her to purchase credits, but backed out when they realized it was a small-scale project dollar-wise. Had Jeanne known that selling (subsidizing) credits was an option from the start, she might have been able to find genuinely interested investors. She is continuing the project and is proud of her progress, but she hopes first-time applicants can receive more information to help them navigate each step in the process. She believes that many more buildings of this size can be saved with such assistance.

Union on Main during renovation

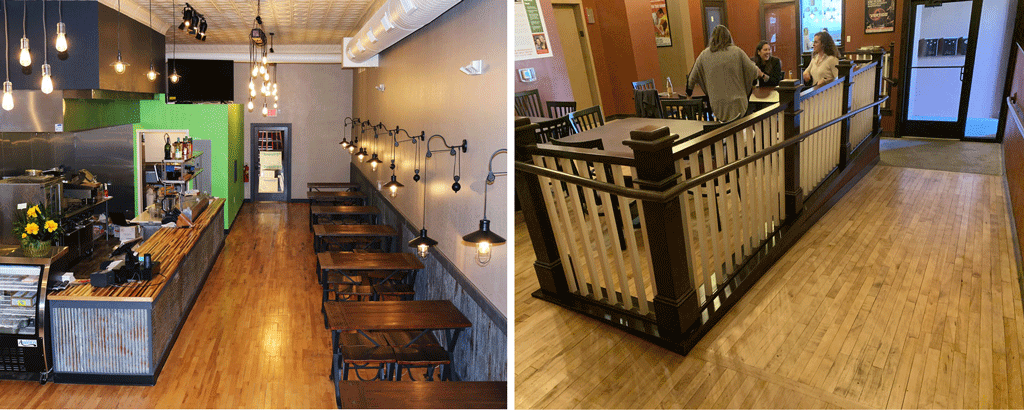

417 Main Street W (Copper Pasty) – Ashland

Before-and-after images of the façade and first floor on 417 Main Street W

While this was a true small-scale tax credit project in scope of work, square footage, and dollar amount, it certainly didn’t seem small to owners Tim Pavlish and Elizabeth Andre, as they (like many of the owners in this article) had to learn the application process, the eligible expenses, project management timelines, etc. However, the project was successful thanks to Tim’s organization, diligence, research, and regular communication with each of the entities involved. He made sure to learn the nuances of the process, which expenses were eligible, when certain timelines affected other ones, and more. The renovation entailed converting the first floor from an antique store into a new dining area and commercial kitchen, making the bathroom ADA compliant, revising the front and rear entrances, and upgrading the stairway. In the basement, they upgraded the electrical system, and installed a new boiler and zone controller to serve the entire building. The upper-floor apartment bathroom was completely remodeled as well.

In total, the project cost $218,843, with approximately $200,000 for renovation costs, $6,800 for architectural fees, and $12,000 for taxes and interest owed. This resulted in nearly $44,000 in credits each for federal and state, for a total exceeding $87,000. In addition to tax credits, they used a downtown building grant and TID funding from the city, and their location in a federal Opportunity Zone allowed them to sell capital at a tax advantage and self-fund much of the project, thus reducing their loan size.

Unfortunately, aside from a few exceptions, the federal credits can only be used to offset tax paid on passive income. Not being a full-time developer, Pavlish and Andre earn the vast majority of their income from W2 wages (earned income), making it hard for them to capture the federal credits in full each year—but the 20-year carry-forward and one-year carry-back for the federal credits (and 15-year carry-forward for state) will eventually allow them to use the full allotment. In addition, his research led him to file an amendment near the end of the project to claim all of the taxes and interest owed during the renovation process, expenses most owners don’t realize are eligible.

Pavlish learned that the process can take time, resulting in strategies like submitting multiple options for planned materials or fixtures to avoid the delays from resubmitting alternatives. When it came time to claim the credits, he pored over state and federal tax code to determine processes, timing, forms, rules, etc. Since his regular accountant didn’t have experience with this type of credit, he had to rely on calls to colleagues and his own research.

Navigating the multiple applications and design review steps–WEDC, WHS, NPS, IRS, and more—was a full-time job. Even simple facts like carry-forward and carry-back were buried deep in the tax code. A one-stop how-to guide covering the entire process, including all entities, would have saved him months of digging. Without such a guide, Pavlish fears many owners will fail to see the big picture or will have to hire a consultant, which would cut into already tight budgets and diminish the incentive to pursue the credits in the first place.

But overall, the tax credits have worked well for him, and he encourages others to explore them. In fact, he recently provided guidance to Jeanne Aspenson, a fellow Ashland property owner pursuing credits on her own building (see the Union on Main case study). What’s more, the renovation to Tim’s building allowed an aspiring entrepreneur to fulfill her dream of running a pasty shop.

Before-and-after images of the commercial kitchen and upper-floor renovations at 417 Main Street W

There you have it: six smaller-scale tax credit projects from around Wisconsin, each with different successes and challenges, united in the fact that historic tax credits were a vital part of making them financially feasible. Hopefully, after hearing from building owners about their experiences navigating the system, the many entities involved in the process for both state and federal tax credits can work together to develop additional how-to resources for realizing small-deal projects without prior experience or paid staff.