By Joe Lawniczak – Wisconsin Main Street

Upper-floor space ready for renovation in Fond du Lac

Upper-floor space ready for renovation in Fond du Lac

Upper-floor housing downtown can conjure up many images. Some might envision seedy, run-down apartments that no one would want to live in. Others might picture large, light-filled loft apartments with tons of character. Some might see modest but well-kept affordable housing for working-class residents, others upscale condominiums they can retire in and have zero yardwork to do, and many an opportunity to live just steps from restaurants, shops, groceries, pharmacies, farmers markets, parks, events and more. There is some truth to all of these when it comes to upper-floor housing in downtowns and historic commercial districts.

Upper-floor housing has been a part of U.S. downtowns since the days our communities were built. It was an age before automobiles, so business owners had their shops on the first floor and lived upstairs. Their daily commute was a flight of stairs. After World War II, the automobile increased people’s mobility, and much of the population moved to the suburbs and commuted to and from their businesses each day. The upper floor living spaces were then either rented out, used for storage or left vacant by the owners who didn’t want to become landlords in addition to being business owners and homeowners.

For several decades, many of these spaces deteriorated, sitting empty and unmaintained, or suffered years of damage from tenants. In some cases, windows were downsized and ceilings lowered, leaving little character and outdated finishes. When vacant, these spaces were not monitored, allowing roof leaks to go unnoticed or animals to take up residence.

The good news is that most of these buildings were built so soundly that they’ve endured. The original window openings, woodwork and ceilings often remained underneath past alterations. In other cases, they were simply left untouched for generations, and all the original character still existed underneath layers of dust. By the 1990’s, many cities began to see a resurgence of property owners and developers bringing these spaces back to life. With this and other downtown revitalization efforts occurring, people began to want to live downtown again.

In recent years, with working from home becoming increasingly common (especially during the COVID-19 pandemic), many people have freedom to live anywhere they choose. Fewer people are tied to a physical office today, but most still want to live in a vibrant area with the amenities they need and want (wifi, broadband, groceries, restaurants, entertainment etc.). The upper-floor spaces of older historic buildings can provide most or all of these amenities, while at the same time having the historic character many people seek.

|

|

Examples of great historic character found in many upper-floor apartments (La Crosse, L, and Ripon, R)

During a time when communities of all sizes are facing a workforce housing shortage, these spaces can provide high-quality, affordable options, meaning that fewer new subdivisions or expensive new roads or utilities need to be developed. And given the proximity to downtown pharmacies, groceries and parks, many empty-nesters and retirees are choosing to live downtown as well. These spaces are often perfect for single professionals who aren’t ready or don’t have the time to own or maintain a single-family home on a large lot.

In this month’s Places Blog, we’ll discuss three ways Main Street programs, downtown organizations and municipalities can and should support upper-floor housing: Encouraging upper floor reuse and development, getting these housing units built and marketing these spaces once they’re ready.

Encouraging upper-floor housing

Many municipalities and Main Street organizations have developed innovative financial incentives to encourage upper-floor development. Rock Island, Illinois, has done a remarkable job of using Tax Increment Financing (TIF) dollars to create downtown housing. The results of the Downtown TIF District Upper Story Housing Program have been impressive over the years, with hundreds of housing units funded. Downtown Rock Island has become one of the most vibrant areas of the Quad Cities. The number of people living downtown was an obvious factor in that revitalization. This link provides

Several communities utilize federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) or Housing and Urban Development (HUD) HOME funding for developing downtown housing. These can often be used for rental rehabilitations, converting existing buildings to housing, property acquisition and new construction. These funds must serve individuals with low to moderate incomes (LMI). Many quality housing developments have been created in downtowns across the state with this funding, bringing vitality back to these areas. In smaller communities, local neighborhood housing organizations and/or Community Action Programs (CAPs) create an annual funding plan to determine which projects they need money for, and they apply to the state for a HOME grant. But in cities over 50,000 population, the municipality receives a set amount directly and is able to determine the use of these funds. Get more information on this program and more.

In Wisconsin, the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority (WHEDA) administers several financial assistance programs for housing, including the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), loans for multi-family housing, revolving loan funds (RLFs) for preservation and rehabilitation of affordable housing and more. Learn more about their many programs here.

Our very own WEDC offers Community Development Investment (CDI) Grants for projects in downtown areas, from renovation or reuse of existing buildings to new infill developments. There must be a commercial component to the project (like retail, restaurants, offices etc.), but the projects can also include housing as well, typically on the upper levels. More information can be found here.

In Beloit, the Downtown Beloit Association offered for several years an Upper Floor Housing Initiative that, among other things, paid for a local architect to develop floor plans for new upper-floor apartments. This service helped property owners see the potential and what would need to be done, code-wise, to utilize these upper-floor spaces.

Often, property owners restore or renovate their upper-floor apartments first to give them the cash flow needed to tackle the ground floor commercial space and exterior façade. What many have found is that by investing more money to create a high-quality space, they can attract a more stable tenant base and thus reduce the cost of turnover and resulting improvements. Communities that provide financial incentives to offset some of those costs can help to encourage more housing in the downtown that meets the needs of local populations.

Upper-floor housing can go a long way toward easing housing shortages for local workers and local industries recruiting new staff. Many of these spaces have been underutilized for decades, but the infrastructure is already there, from utilities to walls, floors and roof. There isn’t a need to acquire new property and extend expensive new utilities or roads to it. The return on investment for a municipality or a Main Street organization to provide incentives for redeveloping upper-floor housing is typically far greater than the return on developing entirely new neighborhoods. Plus, the people living in these upper-floor units are usually far more apt to eat, shop and entertain downtown, thus helping local businesses and enlivening the heart of the community.

Getting upper-floor housing built

Designer and contractor looking over an upper-floor space ready for renovation in Fond du Lac

Designer and contractor looking over an upper-floor space ready for renovation in Fond du Lac

While there are code, life safety and accessibility issues that arise when renovating any building, these issues are not any more restrictive for existing buildings than they are for constructing a new building. In some cases, especially with historic buildings, they may even be less restrictive. There are many factors that determine what code requirements will be triggered—too many to cover in this one article, so we will instead highlight some of the key things that a property owner may encounter or need to know when creating upper-floor housing.

- What is the current use of each of the spaces in the building (each floor, and parts of floors if uses differ)?

- What is the square footage of each of those spaces?

- What is the occupant load (capacity) of each of those spaces?

- If a space is vacant, what was the last known use of the space?

- What type of construction is the building made of (walls, roof, ceilings, structure)?

- Is the property individually listed or deemed eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, either individually or as a contributing building in a historic district?

When looking at the upper-floor spaces, knowing what the most recent use of the space was is very important. If the last use was residential, then it’s possible that fewer code requirements will be triggered. But if the previous use was office or storage, then converting it to residential will often mean having to bring the space up to current code.

The next factor is the level of alterations being planned. Items such as sprinklers may not be required for repairs or minor alterations, while more in-depth alternations may trigger a need to make these upgrades. Since most upper-floor residential units are located above commercial spaces, they typically need to be separated from the commercial spaces by fire-rated ceilings and stair enclosures (and sometimes sprinklers), depending on the hazard category of the other uses and the type of materials the building is made of. For instance, a retail shop has a lower hazard rating than a manufacturing business, and a building made of wood framing is less fire-resistant than one made of concrete. These factors will determine the types of fire-safety measures needed.

Another factor affecting code requirements will be the square footage of the planned residential areas relative to the commercial areas of the building, as along with the number of units being planned. Code requirements may be more restrictive for a project that includes housing rather than just commercial or public uses. If more than 50% of the interior square footage of a building with three or more dwelling units is remodeled, all of the housing units must be brought up to code. If it comprises fewer than three units, or if only 25% to 50% is being remodeled, then only the areas being remodeled need to be made compliant. If less than 25% is being remodeled (and fewer than three units), then only doors, exits, entries and toilet rooms need to comply.

Regarding accessibility, a few factors come into play. If the building is only two stories with residential on the second floor, it generally does not need an elevator. But if the building is three stories or more, with residential on the upper floors, an elevator may be required. A few ways around this for existing buildings include:

- Using what’s called the “Disproportionality Rule”, which states that a building owner only needs to spend 20% of the total project cost on accessibility improvements—so if an elevator would otherwise be required, but it would amount to more than 20% of the entire project cost, they could instead make other accessibility improvements until the 20% is met

- Installing an accessible unit on the first floor (ideally in the back or on the side, thus allowing the main first-floor space to remain commercial)

- On a three-story building, making the living units two-story lofts so that the main entrance into each unit is at the second floor

Some general layout and design issues to consider are: all bedrooms should have an exterior window; exterior windows generally cannot be added on walls that are above an adjacent shorter building; there typically need to be two stairwells that lead directly outside available to each unit; and the entrances to stairwells must be as far apart as 50% of the overall length of the building so a 100-foot-long building would need exit doors at least 50 feet apart).

The Preservation League of New York State published a manual for developing upper floors, which can be found here.

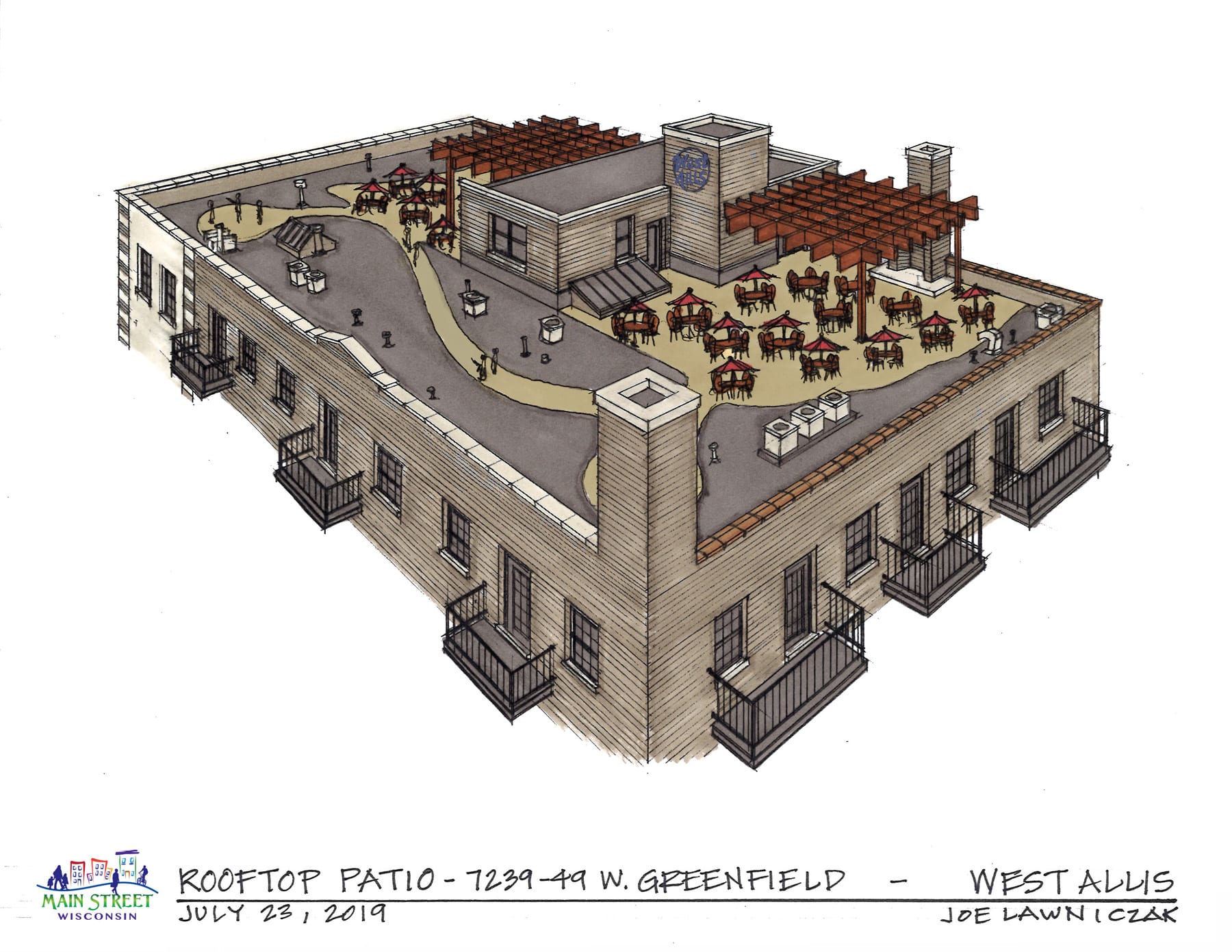

Lastly, providing access to outdoor spaces in upper-floor housing is highly recommended whenever possible—a feature whose value has become even more apparent while staying at home during the pandemic. Adding private balconies or shared rooftop patios can make being quarantined to one’s home a lot more pleasant.

Rendering showing balconies added to the upper floor and a rooftop patio added to the roof of a building in West Allis

Rendering showing balconies added to the upper floor and a rooftop patio added to the roof of a building in West Allis

Marketing downtown upper-floor housing

Once a good selection of upper-floor housing exists in a district, it should be promoted and marketed as an asset of the community. Being able to show potential businesses, residents, employees and retirees that there is a vibrant and unique residential community downtown can be huge for attraction efforts.

In New York state, Downtown Albany and Capitalize Albany teamed up to create a comprehensive upper-floor residential marketing campaign and website called Look Up. The website lists current and planned residential units in the district, the benefits of living downtown, an overview of the downtown residential initiative and a list of resources available to property owners and developers.

Upper floor residential marketing campaign in Albany, New York

Upper floor residential marketing campaign in Albany, New York

We’ve probably all seen or attended “Showcase of Homes” tours in our communities. Most of these highlight new homes built in suburban developments. But in recent years, tours of historic homes and unique upper-floor spaces have increasingly been featured in these tours. Downtown La Crosse hosts annual “upper living” tours. Greenville, Ohio, has upper-floor tours as part of their First Friday events in the month of May. And several communities include upper-floor spaces in their Wisconsin Main Street Downtown Open House itineraries.

Upper floor housing tour in La Crosse

Upper floor housing tour in La Crosse

So by encouraging, building and marketing downtown upper-floor living, Main Street organizations and municipalities can help to create vibrant historic neighborhoods within their downtowns.