By: Joe Lawniczak, Wisconsin Main Street

June, 2022

We’ve come a long way – do we remember the struggle? Are there lessons learned?

Triangle Market in downtown Madison.

The other day, I was watching the classic movie “Scarface.” There’s one part of the movie where Al Pacino goes to a run-down hotel room in South Beach, Miami. When “Scarface” was filmed in 1983, the entire district was deteriorated and in desperate need of preservation. Today, South Beach is a glamorous mecca, known for its iconic, historic, art deco hotels, its glitzy nightlife, and its high-end restaurants and boutiques. The run-down hotel in the movie is one of those now-famous art deco hotels. It struck me that “Scarface” wasn’t filmed back in the 1950s or ‘60s. This was during my teen years, just 39 years ago.

I’ve seen recent photos of CBGB, the legendary New York night club where nearly every punk musician across the globe has played at least once. It was a run-down dive with filthy bathrooms in a rough part of town, but it was iconic. Today, it’s a high-end fashion store and is next-door to an upscale franchise retailer. Many of the old musicians and patrons wouldn’t recognize it if they walked by.

Last month, I was in Staunton, VA, for a tour of this stunningly preserved and vibrant historic gem. This city has been on my bucket list for decades because of its amazing downtown, nestled in the mountains. It looks today like an area that no one would ever have questioned saving. So, I was surprised to learn of the almost-constant struggles that advocates had, from the 1950s through the 1990s, trying to convince local leaders not to demolish entire swaths of downtown. It reminded me of similar stories in Savannah, GA; Providence, RI; St. Augustine, FL; South Beach and countless other historic cities that are now world-famous tourist destinations—only because citizen groups, decades ago, rallied and fought to save them from the wrecking ball.

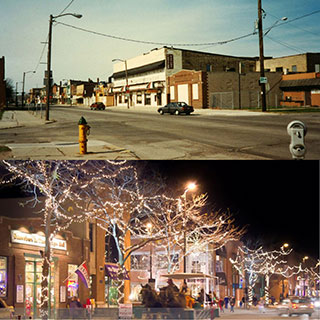

Broadway District in Green Bay in 1995 (top) and after revitalization efforts began (bottom)

Closer to home, I vividly remember the Broadway District in Green Bay, as recently as the mid-1990s. This area had suffered for decades from massive lack of investment, deterioration, crime, poverty and neglect. It was known for its pawn shops, adult bookstores and dive bars. No events were held on Broadway. Few parents let their kids go there alone. But in the mid-1990s, a group of Broadway businesses banded together to create On Broadway, Inc., and the area became a designated Main Street district. Slowly, they worked to build confidence in the area from the private sector, the city began investing in streetscape improvements, and building by building, the area eventually became one of Green Bay’s top downtown destinations. It is now home to breweries, boutiques, public art, restaurants, housing, events and one of the state’s most successful farmers markets. This would have been unthinkable in 1995.

Today, across Wisconsin, we see tiny rural villages, quaint small towns, and larger cities all with thriving downtowns. Even the smallest of our communities have murals, public art, farmers markets, outdoor concerts, breweries, wineries, boutiques, B&Bs and more. Old factories, warehouses, gas stations and schools are being converted into downtown housing, retail, commercial or entertainment spaces. No longer do we need to preach about the importance of downtowns or historic buildings. People seem to get it—finally. It truly seems to be a heyday for our communities.

But with all of this success comes challenges. And several key challenges need to be addressed now, before it’s too late. First and foremost: We need to remind people of the tremendous amount of work it took to get to this point. Even those of us who lived through the struggles are prone to forget how hard it was. We get so used to the way things are now, we rarely stop to think back.

It is also my opinion that we need to reign in much of the overbuilding occurring in many cities today. I am extremely proud of the 35 years that Wisconsin Main Street has worked in historic commercial districts, and of the millions of hours invested by dedicated local staff and volunteers. Together, we’ve transformed downtowns into places where people want to be instead of places only for the less fortunate. But with that, we’ve also made many of them unaffordable to a large segment of the population. And while I will always believe that places like Broadway in Green Bay desperately needed to be revitalized, I still have friends from the area who long for its grittier days.

Admittedly, we’ve lost a lot of the dents and dings and rust that made downtowns unique even as we have helped them thrive in communities, both large and small, throughout Wisconsin. But in some aspects, a lot of them are beginning to look the same. Many downtown areas seem as safe and tidy as a suburban shopping center, as we’ve cleaned away most of the patina and character. While some of that cleaning was needed, have we gone too far in that effort?

The effects of housing in our districts

The pandemic has forced us to learn to function remotely. This means many people can live almost anywhere and are not tied down to an office or a specific location. Our downtowns are reaping the benefits of that, because they have so many of the attributes people are looking for today, such as culture, convenience and recreation. But at the same time, some negative side effects are resulting.

In many communities, there is an enormous lack of housing, especially affordable workforce housing. And as cities race to add new single-family suburban or large-scale multifamily developments, they often forget about the vacant or underutilized upper floors of downtown buildings that are prime for this type of development.

In many larger cities, even though huge numbers of new housing units are being built to meet the demand, it’s important to realize that living downtown is hip and trendy now. While this new development boom may satisfy current demand, I fear that once this trend subsides, many of our cities are going to be stuck with a glut of empty residential buildings littering downtown. Renovating existing upper floor spaces is far more sustainable because it doesn’t require new construction or new land, and those spaces already are served by utilities.

Large scale housing developments like this may be filling the current need for downtown residential, but many of them are replacing the Main Street-scale buildings that made downtown desirable in the first place. And if this current market for downtown housing wanes, will our downtowns be filled with vacant condo and apartment towers?

In addition, far too many of these newly constructed housing developments require the demolition of smaller Main Street-scale buildings. But it is these smaller buildings that give downtowns their pedestrian scale and friendliness. They are what make downtowns desirable in the first place. And ground floor spaces in these existing buildings are often more affordable to local businesses than similar spaces in new developments. They also tend to have more character.

Both the lack of housing and the overbuilding of new upscale developments are driving housing prices skyward, forcing many of the people who work in the downtown restaurants and retail businesses to look outside of the downtown area just to find affordable housing. This then taxes our public transit or transportation infrastructure, and the extra commute times—and additional gas—needed by workers can negate any other green or sustainability efforts a community might undertake.

And for those who decide to live downtown, especially in upscale apartments or condos, the convenience of living downtown can be offset by the additional noise from events, concert venues, outdoor dining, etc. These are all things that make our downtowns desirable and some even give them a bit of that positive urban character, but many new residents begin to complain about the noise, which creates friction.

Trends are not forever

Another trend that is having an impact on downtowns is the popularity of home improvement television shows. As a design specialist working with property owners on their façade renovation designs, I see the influence of these shows regularly. On the surface, that’s a good thing because it gets people thinking about design, and most renovations they feature are vast improvements over what was there. But in some cases, they show things that would be inappropriate from a preservation aspect—such as demolition of original windows or painting exterior brick—or they do things that are trendy at the moment, such as using ship lap or bold colors.

I am both a designer and a preservationist, so I don’t shy away from introducing bold or modern elements when they are appropriate. In most cases, I consider the character of the building, the business and the district when determining what is right or wrong for a particular renovation. But I’ve noticed that a lot of property owners are now asking for the same or similar features over and over again, regardless of the building, because they saw them on television.

It’s important to realize that by nature, trends change, and things that are in style now may look outdated in a few years. A perfect example is happening in a community that I won’t name. This city is doing a lot of great things downtown, and a lot of property owners are making building improvements. But many of them have asked me to design their renovation using black paint on the brick. In many cases, they want this on previously unpainted brick, which, in this climate, is not appropriate. The ironic thing is in this same community, back in the 1970s, almost an entire block of buildings was painted black and it was an eyesore for decades until the paint was finally stripped off less than 10 years ago. Just 10 years ago, yet no one seems to remember it. That reinforces my earlier point that we need to continually remind people of what our downtowns were like before this most recent revitalization boom. That way we can appreciate how far the effort has come, and we can avoid making the same mistakes twice.

An entire block of black paint, applied during the 1970’s when it was trendy, is being removed after decades of it looking dated and deteriorated. We need to resist the urge to follow similar current trends that will also be outdated soon.

Embracing technology while preserving the past

Energy efficiency initiatives have also had an impact on preservation recently. Energy efficiency and sustainability are vitally important for countless reasons, but often, initiatives can have unintended consequences. For example, I recently read about a new federal grant that will help to fund replacement of windows in low-income households if the windows are five years old or more. Five years. That is the threshold for replacement. All that is doing is contributing to the throwaway mentality of our society. And the fact is: Throwing five-year-old windows into a landfill and replacing them with new ones that require all new materials and energy to manufacture is likely worse for the environment than any air infiltration that might occur in the existing windows. Chances are the existing windows, especially the older, wood-framed type, can be repaired and/or have storm windows added, which can create just as much energy efficiency as most replacement windows. The International Energy Conservation Code also rewards owners for replacement over and above window repair or restoration. This needs to change. The Environmental Protection Agency addresses this contradiction here.

In many cases, it might actually be the lack of insulation that is causing energy efficiency issues, not the windows. The problem is: Installing insulation improperly can harm historic buildings. Many energy codes also go too far, in my opinion, in making buildings too airtight. Buildings need to be able to breathe. If they’re too airtight or too insulated, not only do they require more artificial ventilation through the HVAC system—which requires more energy to run—but the lack of any natural airflow in our walls can aid in the formation of mold and mildew in damp areas.

In some cases, it is the preservation advocates themselves who create problems for preservation. While it is absolutely important for a local design review board to protect the historic integrity of structures, the boards can often become overzealous and unwilling to compromise. Solar panels are a good example. In many cities, local ordinances allow them as long as they are not visible from the primary façades, and as long as they don’t damage or obstruct important architectural elements. But some review boards don’t allow them on historic structures at all. Compromises need to be reached in cases such as these, because items such as solar panels can have a positive impact on our reliance on nonrenewable resources. If it can be done in a less visible way, then by all means, they should be allowed. If preservationists lose the support of energy-conscious citizens, they will be losing a natural ally, which will make preservation advocacy that much harder. Plus, most historic buildings have had to embrace other new technologies in the past, such as electricity and plumbing. Things like solar panels should be no different.

Building codes and the code officials who review them have an enormous impact on historic buildings and preservation, especially in mixed-use commercial buildings. Despite the fact that there are hundreds of existing buildings for every new one built, most training for code officials focuses solely on new construction. Even many architects are unaware of all the options and code paths that exist for renovations to existing buildings. Because of that, far too many local building inspectors and state code reviewers force new building standards on building renovations. This can make projects with already-tight budgets become financially infeasible and result in vacant buildings, storefronts or upper floors. Such vacancies are not only detrimental to the vibrancy of downtown, they also pose a safety concern for fire and police departments.

For this reason, the Association for Preservation Technology has created a technical codes committee and a specific task force focused on codes related to Main Street districts. Among other things, this task force has developed a three-day virtual code workshop for existing Main Street buildings. It will be held August 2-4, 2022, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. CDT, each day. The three days will include a series of 45-minute sessions and one two-and-a-half-hour deep dive segment. The sessions are open to anyone, including code officials, architects, contractors, property owners, developers and Main Street practitioners across the country. More information and registration for the workshop can be found here: https://tinyurl.com/58fybxzt

In conclusion

A 1930s gas station in Gordon, Wisconsin was simply repainted to show locals its potential for reuse. Images by Brian Finstad

In spite of all the challenges, I’ll be the first to admit that sometimes we can overthink historic preservation. When faced with a threat to historic buildings, we tend to panic or make it far too complicated. But consider the example set in tiny Gordon, WI—population 600—where a 1930s catalogue-order gas station that was the last of its kind was deteriorating. The only solution from local citizens and leaders seemed to be demolition. Then, a small group of citizens banded together and decided, simply, to repaint the exterior. The roof, structure, site and interior still needed a lot of work, but the fresh coat of paint allowed people to see the building’s potential. Immediately, people began to talk about how to save it rather than how long before it would have to be demolished.

These are the key issues facing historic preservation today, as I see it. Hopefully, this column has been thought-provoking and provided some ideas that you can take away as a village or city leader, preservationist, property owner, planner, code official or advocate. Ideally, the downtown revitalization trend we’ve seen over the past few decades will continue for the foreseeable future, and some of the unintended or less-favorable consequences will be addressed at all levels to make the results more sustainable and accessible for all.